Why There Should Be No More Sorting at Hogwarts

The Sorting process is a rite of passage for Harry Potter fans. For many, it legitimizes their fandom. Conventionally, the first question you ask any Potter fan you’ve just met is “What House are you in?” And when you come across someone who’s in the same House as you, there’s an unspoken sense of camaraderie. Houses act as personal and collective identity markers – people often show a high degree of pride for their Houses. The Gryffindor, the Slytherin, the Ravenclaw, and the Hufflepuff will all attest that their Houses are a reflection of their personalities. People view their Hogwarts House as symbolic of their values, attitude toward others, and approach to life.

Personally, when I first read Harry Potter, growing up as a child in the late 1990s and an adolescent in the early 2000s, the Sorting process was one of my favorite features of the wizarding world that J.K. Rowling had created. I’m definitely not alone in that regard – a lot of us grew up yearning to attend Hogwarts, and the House system made that seem possible; in our minds, we were already there.

Literature can have an impressionable effect on young children. As a ten-year-old, I wishfully wanted to be in Gryffindor because that was where all our heroes resided. As a 15-year-old, I thought that Ravenclaw perfectly aligned with my personality and worldviews. As an adult, I’m secure in my Hufflepuff-ness. However, recently – after retaking Pottermore’s quiz and others – I’ve begun to wonder whether I really am a Ravenclaw instead. In Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, Harry developed a negative impression of Slytherin due to his interactions with Draco and Ron – and earlier, Hagrid. What this all demonstrates is that our values are malleable, and our experiences influence how we see the world around us. It’s also indicative of a problematic system of categorizing children based on vast, generalized descriptors such as bravery, intelligence, or loyalty.

Hogwarts’ Sorting Hat and Pottermore’s Sorting quiz are both based on statistics. They attempt to categorize people into one of four Houses based on their personalities. However, personality traits are not categorical – they exist on a continuum and can overlap with each other. In terms of the Hogwarts Houses, this means that most people have a little bit of all the Houses in them, to varying degrees. The Sorting process simply divides students into Houses based on probabilistic inferences. It measures the potential in students – so that a student Sorted into Ravenclaw has more academic potential than a student Sorted into Gryffindor – but discounts the fact that people can and do change throughout their lives.

There’s also the issue of Hatstalls. Pottermore defines a Hatstall as “an archaic Hogwarts term for any new student whose Sorting takes longer than five minutes,” citing Minerva McGonagall and Peter Pettigrew as “true Hatstalls.” The existence of Hatstalls gives further credence to the notion that Sorting isn’t a black-and-white issue. As Sirius said in the film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, “We’ve all got both got light and dark inside us. What matters is the path we choose to act on.” This parallels Dumbledore’s statement that “it is our choices… that show what we truly are” (CoS 18) and conveys that while our Houses are a reflection of us, they don’t define us.

When it comes to Sorting, there are little bits of all the Houses in most of us. The only question is, how much? If Sorting a person into a Hogwarts House is anything like evaluating their personality, then it’s not something that can be categorized. The problem is that Sorting, by its nature, is a categorical activity. To clarify what I mean by this, consider the notion that gender and sexuality are spectral and can be placed on continuums. If gender is non-binary, then it follows that sexuality is non-trinary. Given that there are only four Hogwarts Houses, Sorting is a less complex issue. The Sorting process can be graphically depicted via a four-quadrant model – which should be familiar if you’ve ever completed any of those online political compass quizzes.

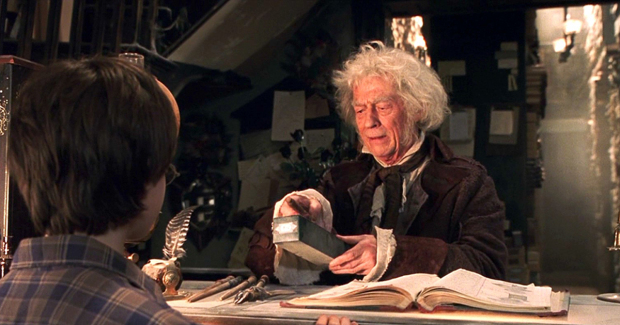

In Sorcerer’s Stone, Ollivander tells Harry that “no two Ollivander wands are the same, just as no two unicorns, dragons, or phoenixes are quite the same” (SS 5). By that same logic, no two Ravenclaws are the same. As a case in point, intelligence comes in many forms. Although the Sorting Hat considered Sorting Hermione into Ravenclaw, Hermione’s bookish idea of “learning and wisdom” is very different from Luna’s curiosity. Furthermore, even Fred and George’s creative intelligence could be considered a Ravenclaw trait.

A lot of the Sorting quizzes in circulation display your results by assigning a percentage to each Hogwarts House – the higher the percentage, the more suitable you are to that House. For example, someone might be 5% Gryffindor, 15% Hufflepuff, 30% Slytherin, and 50% Ravenclaw. Since Ravenclaw constitutes the highest proportion of suitability, the Sorting Hat would place that person into Ravenclaw. This also slightly explains the atypical trajectories of characters such as Peter Pettigrew or Percy Weasley.

Throughout the Harry Potter books, there’s a tendency for members of the same family to be Sorted into the same House. This suggests that there is a genetic factor, among a multitude of other factors (e.g., environmental), that can account for a person’s likelihood to be Sorted into any Hogwarts House. When it comes to pure-blood families, it’s implied that most children are homeschooled. This would reduce any environmental influences and increase parental biases. For instance, consider Draco Malfoy. Pre-Hogwarts, he was definitely homeschooled and was conditioned to favor Slytherin because his parents would have instilled that in him.

Anomalies do occur, though, such as Sirius. In his case, more than a disdain for the Dark Arts, I think that the favoritism that was shown to Regulus played a part in his decision to diverge from family tradition. In Harry’s era, the Patil twins were both Sorted into different Houses – Padma into Ravenclaw and Parvati into Gryffindor. I suspect that Parvati was Sorted into Gryffindor because she had a desire to distinguish herself from Padma and be seen as her own person. Again what this demonstrates is that it is our choices that matter most.

There’s a psychological phenomenon known as the Barnum effect that speaks to the negative issues that arise from the start-of-year Sorting Ceremony at Hogwarts. Individuals fill out a pseudo-psychometric questionnaire that is said to be able to determine their personalities, but the results that they’re given contain vague, generalized statements that could apply to anyone. The Barnum effect occurs when people place too much importance on these statements. This phenomenon is not dissimilar from the importance that people place on their Hogwarts Houses.

In a study from 2015, researchers compared the Hogwarts Houses to the “Big Five” factors of personality: “Openness,” “Conscientiousness,” “Extraversion,” “Agreeableness,” and “Neuroticism.” The study concluded that people displayed traits typical of the Houses they were in but also noted that this could have been attributed, in part, to a self-selection effect.

The authors also found a correlation between the personality of each fictional House and the people who reported that they wanted to be in it, regardless of where they were actually placed.

This implies that some people select Hogwarts Houses based on the traits that they aspire to possess, rather than the traits that reflect who they are. According to J.K. Rowling, the Sorting Hat has never been wrong. But throughout the Harry Potter series, we encounter characters whose personalities are seemingly incompatible with the Houses that they’re in – e.g., Percy, Snape, and Wormtail. In Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Dumbledore tells Snape, “You know, I sometimes think we Sort too soon” (DH 33). Moreover, Gryffindor doesn’t have a monopoly on bravery, no more than Hufflepuff has one on loyalty. The House system places unnecessary pressure on Hogwarts students to live up to the traits stereotypically associated with their Houses and has a self-fulfilling effect on their personal development.