“The Faerie Queene” and the Fifth “Strike” Novel: “Troubled Blood”

by Dr. Beatrice Groves

J.K. Rowling (Robert Galbraith) has recently released the title of her/his forthcoming novel (which will be released on September 15): Troubled Blood. It was Nick Jeffery who first suggested that the title might be taken from Edmund Spenser’s epic poem The Faerie Queene. The phrase appears in the first book of the poem, as the Redcrosse Knight, in a crucial moment, is about to kill himself, having unwittingly entered the Cave of Despair. But although I’ve written elsewhere on possible links between Harry Potter and The Faerie Queene and this is an important passage in the most well-known book of the poem (most readers, to be brutally honest, do not get beyond Book I), it still seemed like a bit of a stretch.

But it has now been proved that Nick Jeffery’s guess was, in all likelihood, a bullseye. For, on the Spring Equinox (March 20, 2020), Rowling changed her Twitter header – and one of the black-and-white images she chose was taken from The Faerie Queene.

The image on the left is entitled “The Blood” and is a modern illustration that creates a faux-medieval/alchemical/symbolic frame around a depiction of the chemical structure of blood. I am interested in Rowling’s use of alchemical imagery and hope to return to this image at a later date, but for now, it suffices to say that it makes it clear that the work to which this Twitter header refers is Troubled Blood (a text she is probably working on in proof stage at the moment).

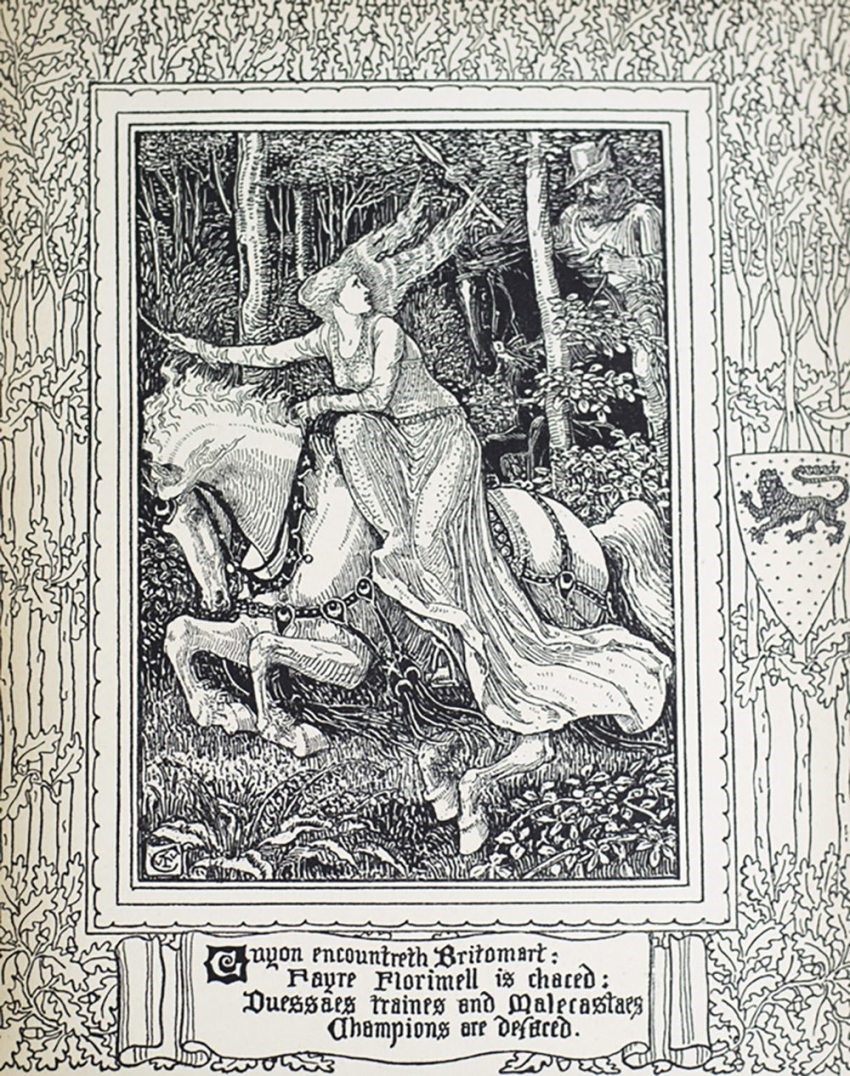

On the right of the header is an image from Walter Crane’s 1896 edition of The Faerie Queene. Walter Crane is an interesting and eccentric figure – he once threw a party for his son Lionel to which seven hundred people were invited (his wife came dressed as a sunflower while he – naturally – came as a crane). The names of his other children – Beatrice and Lancelot – suggest his literary tastes and after revolutionizing the printing of children’s books, he turned to more classical texts and created books such as his Faerie Queene: one of the most beautiful print works of the arts and craft movement.

The image that Rowling has chosen shows the fleeing figure of Florimell. Florimell is a figure I have written about previously in reference to Harry Potter, for she is an interesting example of the way in which Rowling draws on Spenser’s allegorization of morality through the visual appearances of his characters. Both writers use doppelgängers to explore the difficulties that beset moral interpretation – and the false and true Florimell are a tempting parallel for the false and true Mad-Eye Moody. Florimell is trapped for a whole book of the poem without anyone realizing she is missing because she has been replaced by the false Florimell. And (as with the real Mad-Eye trapped in his deep chest) she remains imprisoned in a deep cave, only to be released at the very end of Book IV.

This Twitter image, however, gives us inconvertible evidence that Rowling is interested in The Faerie Queene – so let’s return to the occasion in the poem where the phrase “troubled blood” occurs.

But whenas none of them he saw him take,

He to him raught a dagger sharpe and keene,

And gave it him in hand: his hand did quake,

And tremble like a leafe of Aspin greene,

And troubled bloud through his pale face was seene

To come, and goe with tidings from the heart,

As it a running messenger had beene.

At last resolv’d to worke his finall smart,

He lifted up his hand, that backe againe did start.” (Book I, canto IX, stanza 51)

Renaissance poets were very fond of the idea of blushes – the blood that rushes to Redcrosse’s face here – as a revelation of true feelings: the heart’s blood acting as a messenger and declaring unspoken thoughts in the face. (Thomas Wyatt’s gorgeous sonnet “The long love that in my thought doth harbour” is a whole poem written around this conceit.) Una breaks in on her knight’s despairing trance and saves him from his attempted suicide – taking the “cursed knife” from his hand. And this moment – in which the hero is saved by his female side-kick – has, surely, a fairly clear possible relevance for the Strike/Robin relationship. (Keep an eye out, likewise, for revelatory blushes).

The image with which Rowling has chosen to point towards The Faerie Queene, however, is not taken from Book I, but from the opening of Book III.

All suddenly out of the thickest brush,

Vpon a milk-white Palfrey all alone,

A goodly Ladie did foreby them rush,

Whose face did seeme as cleare as Christall stone,

And eke through feare as white as whales bone:

Her garments all were wrought of beaten gold,

And all her steed with tinsell trappings shone,

Which fled so fast, that nothing mote him hold,

And scarse them leasure gaue, her passing to behold.Still as she fled, her eye she backward threw,

As fearing euill, that pursewd her fast;

And her faire yellow locks behind her flew,

Loosely disperst with puffe of euery blast:

All as a blazing starre doth farre outcast

His hearie beames, and flaming lockes dispred,

At sight whereof the people stand aghast:

But the sage wisard telles, as he has red,

That it importunes death and dolefull drerihed.So as they gazed after her a while,

Lo where a griesly Foster forth did rush,

Breathing out beastly lust her to defile:

His tyreling iade he fiercely forth did push,

Through thicke and thin, both ouer banke and bush

In hope her to attaine by hooke or crooke,

That from his gorie sides the bloud did gush:

Large were his limbes, and terrible his looke,

And in his clownish hand a sharp bore speare he shooke.” (Book III, canto I, stanzas 15-17)

The white horse that Florimell rides must have caught the attention of those who watch Rowling’s Twitter headers – for the succession of white horses that were prancing across it in 2018 enabled us to guess a crucial aspect of Lethal White. Florimell’s appearance on a “milk-white Palfrey” at this point in the poem may have drawn Rowling’s attention (and could it even suggest a link back to Lethal White?) but I suspect it is more relevant than she is fleeing.

Florimell is the woman who, arguably, has the worst time of any in this poem (and that is up against some pretty stiff competition). She spends much of it fleeing potential captors – and escapes each one only to fall into the hands of another. Her final “rescuer,” Proteus incarcerates her in an undersea prison for over an entire book. On the upside, she succeeds in evading all her would-be attackers and ends up marrying the man she truly desires, Marinell. Nonetheless, Florimell spends an extraordinary amount of The Faerie Queene attempting to escape unwanted male attention, and the depth of her danger in the passage quoted above is underlined by Spenser’s allusion to Ovid’s account of Apollo’s pursuit of Daphne in which she escapes rape only by turning herself into a tree (see Golding’s famous translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, 1.642-65).

The abuse of women has been something of an underlying theme of the Cormoran Strike novels so far, from Robin’s rape at university to the horrors of Career of Evil and Matthew’s assault of Robin in Lethal White. The Ovidian “rape” of Leda by the swan seems, likewise, to be behind the naming of Strike’s mother (as well as the swan-motif of Lethal White).

If the choice of Florimell for Rowling’s header, therefore, points to that character, rather than simply to the poem as a whole, then it looks as though this sexual violence is set to continue, although we can hope that Galbraith’s female characters, like Florimell, will evade those who seek to harm them.

We’ll have to wait until September 15 to discover this image’s precise relevance but it seems certain that The Faerie Queene will be turning up in Troubled Blood in some guise or another. Maybe Rowling will be using it for the epigraphs of her new novel (as she did with Ibsen in her last) and – with over 10,500 lines to pick from – she’d be spoilt for choice.

Dr. Beatrice Groves teaches Renaissance English at Trinity College, Oxford and is the author of Literary Allusion in Harry Potter, which is available now. Don’t miss her earlier posts for MuggleNet – such as “Rowling’s Goblin Problem?” – all of which can be found at Bathilda’s Notebook. She is also a regular contributor to the MuggleNet podcast Reading, Writing, Rowling.