Snake Woman in the Ivory Tower

This piece was written to mark the publication of Lana A. Whited’s The Ivory Tower, Harry Potter, and Beyond, but it also marks a celebration of the work of the British novelist Lynne Reid Banks, one month after her passing. Lynne Reid Banks’s young adult novels were some of my favorites as a teenager and I was fascinated to discover in one of her less famous novels, Melusine, a possible source for the Wizarding World. Reid Banks, who shared her birthday with Shakespeare’s Juliet and Harry Potter, died on 4 April 2024.

Lana A. Whited, who brought out the first scholarly Harry Potter anthology back in 2002 with her first Ivory Tower collection, has just published a follow-up collection of twenty-one essays: The Ivory Tower, Harry Potter, and Beyond: More Essays on the Works of J. K. Rowling. According to Cecilia Konchar Farr’s review, this new collection is ‘filled with erudition and insight, brightened by whimsy and playfulness. It is Harry Potter studies at its best!’ I have just received my copy and I am looking forward to reading all the essays – in particular those on Harry Potter’s classical allusions, medieval sources, Shakespearean echoes, narrative mirrors, literary alchemy, story turns, and settings. These essays explore Harry Potter in depth but also look beyond into Fantastic Beasts, The Cursed Child, The Ickabog, Strike, Casual Vacancy, and The Tales of Beedle the Bard. My essay in this collection – which Professor Whited was kind enough to include – argues for the importance of other literary and religious versions of the snake woman to the presentation of Nagini in both Harry Potter and Fantastic Beasts. My chapter explores the importance to Nagini’s story of the mythic hinterlands of snake women in the Book of Genesis, Indian Naga, Chinese and French folktales, and John Keats’s poem Lamia. It focuses in particular on the importance of the medieval French story of the fairy Melusine (a little-known version of the snake woman myth) in The Crimes of Grindelwald’s rewriting of Nagini as benign.

Rowling has spoken of how she used local mythologies and traditions to bring the Parisian setting of Crimes of Grindelwald to life. Melusine’s myth is one such story, and a clue of its importance has been hidden as an Easter egg in the script where the reader (unlike the watcher of the film, where this character remains unnamed) will read the name Melusine.

In the legend of Melusine, a man meets a beautiful woman by a forest fountain, falls in love with her, and unwittingly marries a fairy with a terrible curse. Melusine brings her husband vast wealth, castles, and many children, but his prosperity and good fortune are secured only by the promise that he will never look at her in the bath. One day he cannot resist peeking and discovers she is somewhat snakey from the waist downwards. Melusine (unlike most other snake women), never harms her husband – instead, it is she who is betrayed by him. The most famous version of her story hales from medieval France which forms an important hinterland for Nagini’s story when we meet her again in Paris in Crimes of Grindelwald as a snake woman and, like Melusine, newly benign.

Melusine is a powerful and equivocal figure and Rowling is not the only modern novelist to be beguiled by her story. To mark the publication of Professor Whited’s collection, I thought I would write this blog, looking at two other Melusine novels – A.S. Byatt’s Possession (1990) and Lynne Reid Banks’s Melusine: A Mystery (1988) – which may have influenced Fantastic Beasts. In addition to their sympathetic engagement with the snake woman, each novel could be a source for wider aspects of Fantastic Beasts – in particular Leta Lestrange’s history and one of the most original aspects of these sequels: the Obscurial.

Possession

Byatt’s Possession was the much-talked-about winner of the 1990 Booker Prize, and it seems highly likely that Rowling has read it. The novel synthesizes every possible version of the snake woman myth and one of these – Friedrich de la Motte Fouqée’s Undine (1811) – creates a striking analog for Leta’s story, and the drowning of her baby brother, in Crimes of Grindelwald. In la Motte Fouqée’s story the water spirit Undine appears as a changeling child to replace the baby that was lost at the beginning of the tale when she (apparently) drowned in the lake: ‘a child who has been borne by the waves far from the home of her birth… and reaches out her tiny hands for help’ (Friedrich de la Motte Fouqée, Undine, translated by Mary MacGregor [London, 1907], 66). Undine is a major source for Possession – an allusion made explicit at the end of the novel when Christabel arrives in France in a storm, like an ‘undine, streaming wet and seeking shelter’ (A.S. Byatt, Possession [London: Vintage, 1991/1990], 352). When finally, the story is named outright near the end of the novel – ‘La Motte Fouqués Undine’ (Possession, 362) – it creates a chime of recognition in the reader who has probably failed to notice until this moment the significance of Christabel’s surname ‘LaMotte.’

Byatt underlines the importance of Undine as a source at the end of Possession because of the revelation that Christabel has had a child, and the mystery as to this child’s fate:

Gode said if you take the shirt of a little child and float it on the surface of the feuteun ar hazellou, the fairy fountain, you may see if the child will grow to be lusty, or if it will be weak or die. For if the wind fills the arms of the shirt, and if the body of it swells and moves across the water, the child will live and flourish. But if the shirt is limp, and takes water, and sinks, the child will die… the vision changes my sense of the shape of events. When I ask myself, now, what became of the child, I see the black obsidian pool, and the lively white shirt going down. (Possession 378-79).

The folk motif of the drowned cloth as a metonymic for a dead baby forms a close parallel with Leta’s Boggart in Crimes of Grindelwald. We see this image twice in the film – firstly in the Defence Against the Dark Arts classroom as the Boggart that haunts Leta and, again, as she tells her story in the Lestrange Mausoleum, conjuring the image ‘that has haunted her all her life’ (J.K. Rowling, Fantastic Beasts: Crimes of Grindelwald [London: Little, Brown, 2018], 236). For Leta, like Christabel, the cloth billowing down through the dark water is metonymic for the baby who has drowned. Throughout the film, as in her own psyche, there is the suggestion (as with Christabel) that she is morally guilty of his death.

Leta’s vision powerfully recalls this folktale motif in Possession, and Leta’s own belief that she is a child-killer renders herself monstrous in her eyes – like the snake woman. When Newt attempts to exonerate her, she replies ‘Oh, Newt. You never met a monster you couldn’t love’ (Crimes of Grindelwald, 236). It is a line that explicitly ties together the internal and external beasts of the series, explaining one reason that Dumbledore might use Newt, a hero who ‘loves the purity of creatures that the world might call monsters’ in order to combat the crimes of Grindelwald. (For more on ‘the beast within’ theme).

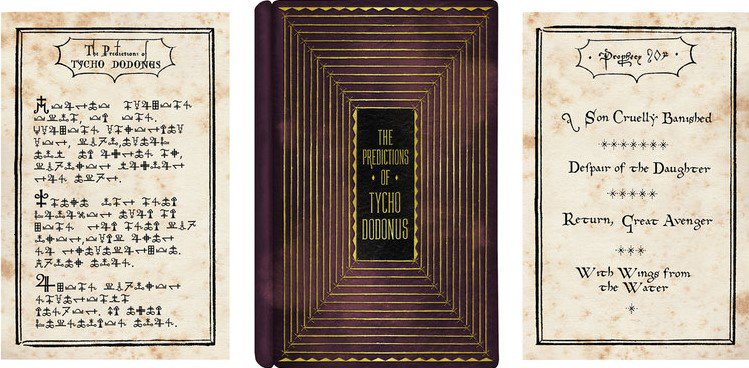

Leta’s unintentional loss of Corvus Lestrange at sea, however, was also the rescue of Credence: the ‘wings from the water’ of which The Predictions of Tycho Dodonus tell.

These ‘wings from the water’ are not those of a member of the Lestrange family, symbolized by a raven (the Corvus whom Kama expects) but a member of the Dumbledore family, symbolized by a phoenix.

The return of a lost child is one of the most fundamental of folk tale motifs – played out in fairytales such as Undine and Shakespearean romances such as The Winter’s Tale and Cymbeline. When I noticed this parallel between Leta, Corvus, and Credence’s story in Crimes of Grindelwald and Christabel’s lost child in Possession, I suspected that the death of Corvus Lestrange would not be the end and that later in the story we would see the return of a lost child. And in the main story, at least, this did turn out to be true. At the end of Crimes of Grindelwald, we are told that Credence is Aurelius Dumbledore, Albus’s brother, but he turns out instead to be a lost child saved from the water – the child of Aberforth.

Melusine: A Mystery

While Possession is a famous modern novel, Melusine: A Mystery (published two years earlier) is somewhat more obscure. It was written by Lynne Reid Banks, who wrote young adult fiction in the 1970s and 80s when there was much less of this genre available (I devoured her as a teenager – and maybe Rowling discovered and enjoyed her too). Lynne Reid Banks’s Melusine is a much darker story than Possession and its modern retelling of the Melusine myth explores the idea of the snake-self as a form of protection for a victim of abuse. Reid Banks uses the medieval myth of Melusine, as Misty Urban has argued, ‘as a provocative metaphor for the splintered self that abused children develop as a coping mechanism to protect them from trauma.’(1) When Roger’s family go on holiday to Poitiers they visit Melusine’s tower in Vendée (a striking stone structure that still stands today). Roger reads in the guidebook that Melusine ‘is a shadowy mythological figure, unknown outside this region… an older tale suggests that she is a direct descendent of the serpent who tempted Eve in the Garden of Eden, and as such the incarnation of evil, which at the same time being the instrument of God. What is common to both tales is that Melusine is the embodiment of both good and evil, being a woman – Eve herself, perhaps – by day and a snake by night’ (Reid Banks, Melusine: A Mystery [London: Puffin, 1988/94], 114). Roger begins to wonder about the girl next door who is likewise called Melusine who habitually wears a T-shirt with a green, diamond pattern.

Melusine, by using the snake woman myth as ‘a provocative metaphor for the splintered self’ generated by trauma has some resonant echoes with the concept of the Obscurial. As fans recognized on the release of Fantastic Beasts it seems likely that the concept is mapped onto Ariana’s history. As many have suggested, it seems possible that Ariana’s Obscurus – her attempt to suppress her magic – was generated by (possibly sexual) abuse. In Fantastic Beasts the Obscurus is explicitly related to the repression of magic in children, and a sexual undertow is given to this repression when it is described how the Obscurus breaks out from within the child at puberty. Reid Banks’s Melusine, therefore, creates a link between Nagini’s snake woman story and one of the most significant additions to the Wizarding World in the Fantastic Beasts franchise – the Obscurial.

In the medieval version of Melusine’s story, there is a denouement in a tower. This is replayed at the end of Reid Banks’s Melusine in a scene that also strongly recalls Harry and Hermione’s fight with Nagini in Bathilda’s bedroom in Deathly Hallows: there is a fight in an upstairs room with a snake, accompanied by the terrible revelation of long-dead woman’s body and the fight ends with a defenestration. In the original medieval telling of Melusine, it is the snake woman herself who leaps from the window of her tower – transforming into a dragon as she leaves her husband forever. In Reid Banks’s Melusine it is the girl’s father, rather than Melusine herself, who leaps from the window and – with his death – breaks his daughter’s ophidian curse. Reid Banks’s story ends by emphatically reinscribing the Satanic imagery where it belongs. It shifts the Satanic imagery of the snake woman from the woman herself to the man who controls her (just as the snake in Eden was itself innocent, only used for evil by Satan). It is a move that seems, likewise, to be echoed in the decisive change between Nagini’s presentation in Harry Potter and Fantastic Beasts.

In Harry Potter Nagini’s ophidian form is one aspect of the Satanic imagery that surrounds Voldemort. But it was always Voldemort, not the snake, who was evil. The revelation of Nagini as a snake woman in Fantastic Beasts, cursed by her snake form, disentangles Nagini herself from the Satanic imagery that always morally belonged not to her, but to Voldemort. By reaching beyond the habitual symbolism of the Edenic snake, and exploring wider and more nuanced snake women mythologies – such as that found in both these Melusine novels – Rowling performs in Crimes of Grindelwald an empathetic rewriting of her own myth.

To buy — The Ivory Tower, Harry Potter, and Beyond: More Essays on the Works of J. K. Rowling, or ask your local library to order!

Citation:

Misty Urban, ‘How the Dragon Ate the Woman: The Fate of Melusine in English,’ in Melusine’s Footprint: Tracing the Legacy of a Medieval Myth, eds. Misty Urban, Deva F. Kemmis, and Melissa Ridley Elmes (Leiden: Brill, 2017), pp.368-87 (380).

Dr. Beatrice Groves teaches Renaissance English at Trinity College, Oxford, and is the author of Literary Allusion in Harry Potter, which is available now. Don’t miss her earlier posts for MuggleNet – such as “Solve et Coagula: Part 1 – Rowling’s Alchemical Tattoo,” – all of which can be found at Bathilda’s Notebook. She is also a regular contributor to the MuggleNet podcast Potterversity.

Writing with cutting-edge literary analysis of the series, Bathilda’s Notebook explores the literature and ideas that have most inspired Rowling, from Shakespeare to Sherlock Holmes.